Francesca Blockeel: Portugal en zijn kolonies. Dekolonisering en teruggave van kunst

Summary: Portugal and Its Colonies. Decolonisation and Restitution of Art

In the sixteenth century Portugal was one of the great powers and, with Spain, a precursor in colonizing areas in Asia, America and Africa. Its imperium covers 500 years and it controlled colonies that now are situated in 53 different countries.

Nevertheless, in the actual debate about restitution of colonial art Portugal is almost never mentioned.This contribution starts with a concise overview of how Portugal

handled its colonies in the three continents consecutively, along with the kind of artefacts that were brought to the metropolis, Portugal as the mother country. As the discussion in Europe focalizes mostly on African art, the Portuguese colonies in Africa

are studied here more thoroughly. In the second half we sketch the current situation of restitution of colonial art in Portugal. First we examine the main position of museum directors and secondly what is going on in the press and on social media. It is obvious that the national identity of the Portuguese, still mainly based on the colonial empire, plays an .important role.

Lies Busselen; De tijd haalt ons in. Hoe het restitutiedebat een lens biedt op een verschuiving in de ‘ontkenning van gelijktijdigheid’

Summary: Time is Catching Up With Us. How the restitution debate offers a lens on a shift in the “denial of coevalness”

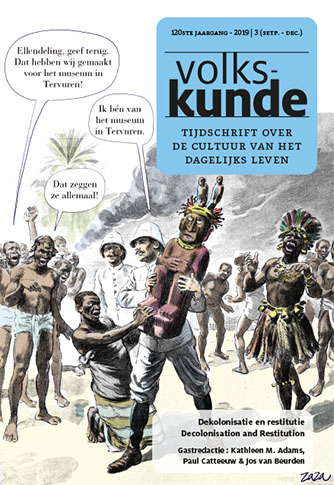

This article offers a theoretical reflection on the unequally shared heritage of former colonies and metropolises. I apply Johannes Fabian’s concept of “denial of coevalness”, a way to see “the other” in another time frame, to the restitution

debate concerning colonial collections in the Belgian and international contexts. The article outlines the historical process of the formation of international legal frameworks in relation to the restitution debate in Belgium in a section that explores the political dimension of these issues.A subsequent museological section examines colonial collections in current world museums, focusing on the Africa Museum in Tervuren and

the National Institute of Museums of Congo in Kinshasa. The article shows how African states remain absent in the Western restitution debate and argues for the “recognition of coevalness” between states in order to achieve reciprocal dialogues. Finally, the article argues that political recognition of the colonial past in Belgium is essential for the

recognition of coevalness of Congo.

Elisabeth Dekker: =tano Toba Saga.. Een menselijk verhaal en het recht

Summary: The Tano Toba Saga. A Human Story and the Law

This essay explores new approaches to reflecting on the future of colonial collections by considering the legal position of former colonies in tandem with a discussion of the Tano Toba Saga, a work of art exhibited as part of the exhibition Power & Other Things:

Indonesia & Art 1835-Now. Drawing on archival materials and cultural property laws, this article lays bare some troublesome dynamics pertaining to contemporary property

rights. In the article I argue that those property rights are marked by deeply ingrained distinctions and racial stratifications pertaining to who is considered human: a painful

legacy that continues to haunt colonial collections. To move beyond such colonial structures, this article highlights how the Tano Toba Saga provides a legal subject historically excluded from humanity, with a voice, a story, and a name.

Valerie Mashman: ‘Looted in an expedition against the Madangs’. Decolonizing history for the museum

Summary:Een toevallig onderzoek van het originele eerste acquisitieboek in het Sarawak Museum onthulde de term “geplunderd tijdens een expeditie” die werd gebruikt om een set van zes huishoudelijke objecten te beschrijven uit een langhuis,

verworven in 1903, van een aftredende Brooke-beheerder, C.A. Bampfylde. Dit leidde tot een zoektocht van een jaar naar deze objecten, op de schappen van het depot van het Sarawak Museum en in de archieven en opslagplaatsen van het Pitt Rivers

Museum, Oxford. Deze objecten – over het hoofd gezien door curatoren en zelden tentoongesteld – komen uit de huishaarden van de longhouses. Het betreft huisraad en daarom onwaarschijnlijke trofeeën van een orlogsexpeditie. De aanwezigheid

van deze objecten in het Sarawak Museum roept dus twee vragen op:waarom zou huisraad als geroofde objecten worden geschonken, en waarom zou een ambtenaar ze

hebben bewaard en weggegeven bij pensionering? Om antwoorden op deze vragen te suggereren door de herkomst van deze objecten te onderzoeken, volgt dit artikel de

carrière van de schenker-verzamelaar.Het analyseert tevens de betekenis van de term “geplunderd” en de implicaties voor het gebruik ervan, en e daaropvolgende reconstructie van de oorlogsexpeditie waarin deze items werden verworven. Aan de ene kant vertegenwoordigen deze objecten een overwinning in oorlogsvoering voor

het Brookeregime en aan de andere kant biedt de aanwezigheid van deze vijf objecten in het Sarawak Museum de mogelijkheid om mondelinge geschiedenissen en koloniale

rapporten te analyseren om de context te beschrijven en te reconstrueren wat er zou kunnen zijn gebeurd met de oorspronkelijke eigenaren, met name vrouwen die vechten om te overleven en worden onderworpen aan het niet aflatende geweld van strafexpedities. Deze objecten dienen als een katalysator voor de stem van de Badeng via mondelinge overlevering over keuzevrijheid, weerstand en onafhankelijkheid tijdens het Brookeregime. Tegelijkertijd wordt de tentoonstelling van deze objecten een complete set van zes, met de mogelijke uitlening of teruggave van 538 | summaries

de geplunderde hoed van het Pitt Rivers Museum.

Jonas van Mulder:Gedeeld erfgoed? Archiefgemeenschappen en de restitutie van kennis

Summary: Shared Heritage? Archival Communities and the Restitution of Knowledge

This paper reviews significant developments in archival science and practice that can potentially offer valuable insights into current debates about decolonizing heritage

collections. In both the professional archival field and amongst archival communities, the calls for partnerships in building and curating archives, expanded digital exchanges,

and greater transparency of archival practices have gained momentum in recent decades. As evidenced by an ever expanding body of research and applied approaches, ‘the archive’ has been zealously mobilized as an analytical and experimental instrument for both analyzing and counteracting the colonization of

knowledge, epistemic regimes, and cultural and social exclusivity inherent in conventional archival praxis. In addition to highlighting a sample of international studies and initiatives, this article also identifies some potential pitfalls and offers observations concerning the impact of digitization, the importance of collaborative research, and the value of dissonance.

Willy Durinx, Paul Catteeuw en Roselyne Francken: De collectie Hans Christoffel in het MAS Antwerpen

Summary: The Hans Christoffel Collection of the MAS Museum (Antwerp)

Hans Christoffel (1865-1962), a young Swiss, enlisted in the Dutch colonial

army at the end of the 19th century. He rose quickly through the ranks to

become the most revered and reviled officer active in the bloodstained

Dutch East Indies. Later, he seemingly turned his life around full circle to

become a pacifist. During and after his service years, he assembled a vast

collection of ethnographic artefacts. After a long-term loan, Christoffel

sold his collection to the City of Antwerp in 1958. Financial concerns

undoubtedly played an important role in this decision, but the sale may

also have been a final endeavour to physically distance himself from the

tangible memories of a violent past. Since the permanent closure of the

Antwerp Ethnographic Museum in 2009, the collection is accommodated

in the MAS, which opened its doors in 2011. The MAS can boast a rich

exhibition history of the Christoffel collection. Moreover, whenever

artefacts from the collection were put on display, the museum did not fail to

refer to the blood-drenched colonial context in which it was partly formed.

In the enigmatic maze that is the MAS online database, however, the artefacts gathered by the Swiss military man are nearly unfindable. A better online visibility of the collection is needed to reach Indonesian stakeholders

and cultural heritage partners as well as an international audience. In 2020, the MAS will therefore create a presentation of some hundred pieces of controversial provenance from the Christoffel collection on the online

platform Google Arts & Culture. And maybe this presentation could lead to talks between the MAS and the source community about a possible

restitution of stolen heritage objects, amongst others important five flags

from Aceh. Many questions will however have to be answered before a

possible restitution will be reality.

Jos van Beurden: Niet alles is roofkunst – Wat te doen met andere koloniale collecties?

Summary: Not Everything is War Booty. What To Do With Other Colonial

Collections?

This essay examines museum de-accessioning patterns in the Netherlands and Belgium to address the extent to which institutions have attempted to return objects to their countries of origin. In particular, this article spotlights several case studies involving more extensive de-accessioning: the Nijmeegs Volkenkundig Museum, the museum of Radboud University Nijmegen (which was closed in 2005, and that of the municipal Museum Nusantara Delft (which closed in 2013). The Radboud University Nijmegen

Museum’s 11,000 mostly-Indonesian items consisted of several collections.

These included its own small 540 | summaries collection, as well as several “subcollections” loaned by missionaries as well as the Beijens collection of

approximately 3,000 items, a loan from the municipality of Nijmegen.

This essay reveals the often troublesome journeys of these subcollections.

The majority of them have remained in the public domain.

An unknown number of items were offered for sale in the art market.

Some have disappeared. With few exceptions, almost no objects have

been returned to their countries or regions of origin. There were neither

networks nor know-how to facilitate this option. Return was not yet in the

air. This is a weakness, that indicates the need for a new approach.

When the Nusantara Museum Delft was obliged to deaccession its

collection of 18,500 items, the idea of return was immediately considered.

But it was challenging to convince the government of Indonesia to accept

this seemingly-generous Dutch offer. A new Director-General for Culture

at the Ministry of Education and Culture in Jakarta resisted the Dutch

return-offer. Apparently, part of the reason for diminished Indonesian

interest in the return was that the Netherlands had not offered a full

collection return: the Netherlands had set aside over 3,500 objects

for the National Collection of the Netherlands and for the Collection

Delft. The Nusantara Museum had urgently to look for interested

museums in the Netherlands, or in the rest of Europe and in other

countries than Indonesia in Asia. Eventually, Indonesia accepted 1,500

objects, selected by their own officials. At the end of 2019, the selected

objects were still in the Netherlands. The essay makes several concluding

observations: In cases involving deaccessioning colonially-collected

objects, we must reconsider regulations requiring that the Dutch

National Collection be offered first consideration as a new home for such deaccessioned objects. In return negotiations, Dutch heritage officials should be more sensitive to cultural differences. Whereas we might presume post-colonial nations are equally interested in how the objects were required, this is not universally the case. Throughout the return-process, Indonesia was not interested how the objects had been acquired (e.g. whether via war booty or other means). Rather, Indonesia sought objects that could fill holes in its own national collection.

Finally, Dutch museum officials were unable to achieve their preference

for the objects to be returned to regional museums in Indonesia, as its counterpart in these negotiations was a sovereign state with its own

priorities.

Placide Mumbembele Sanger: La restitution des biens culturels en situation (pos)coloniale au Congo

Summary: De teruggave van cultureel erfgoed in (post)koloniale situaties in Congo: tussen politieke kwesties en behoud van het erfgoed

Macrons toespraak over de teruggave van Afrikaans erfgoed heeft in

sommige musea, in de wereld van handelaars, verzamelaars en in de westerse publieke opinie emoties losgemaakt. Opmerkelijk is echter het feit dat het debat voor het eerst door een Europees staatshoofd wordt aangezwengeld. Wat de Democratische Republiek Congo en haar voormalige koloniale macht België betreft, eisten sommige Congolese politieke leiders in 1960, in het kader van de onafhankelijkheidsonderhandelingen, de repatriëring van de collecties

van het Belgisch Kongo Museum in Tervuren, dat zich daartegen had verzet. Als België in de jaren zeventig een honderdtal voorwerpen

terugstuurde naar Congo, een honderdtal voorwerpen die het beschouwt als een schenking aan de Zaïrese autoriteiten, is het een overwinning dankzij de toespraken van president Mobutu in 1973 op het derde congres van de International Association of Art Critics in Kinshasa en op de 28ste Algemene Vergadering van de Verenigde Naties in New York over de teruggave van cultureel erfgoed aan Afrikaanse landen. Anderzijds wordt in dit artikel uitgelegd dat, ondanks de belangstelling die Macrons toespraak

over de teruggave in de wereld heeft gewekt, het debat in de DRC nog

niet open is in de academische, politieke of publieke opinie.

Dit artikel herinnert eraan dat het verzoek om teruggave van culturele

goederen door Afrikaanse landen gerechtvaardigd is. Ook wordt een

beroep gedaan op kunstwerken om te circuleren tussen het Noorden en

het Zuiden vice versa, wat dialoog en samenwerking tussen musea vereist.

Een van de essentiële voorwaarden voor deze dialoog, zoals Sarr en

Savoye in hun verslag zo goed hebben beschreven, is ook om de

betrekkingen opnieuw te overwegen en zo een “nieuwe relationele ethiek”

tussen Afrika en Europa te creëren.