- Marit van Dijk, Hester Dibbits, Jet Bakels & Sofie De Ruysser – Observations: Our every day Life with Birds

- Inge van der Zee-Minkes – Aaisykje: from picking to cherishing

- Hubert Slings – ‘Die vinken en keepen wil vangen, die zinge geen psalmen of gezangen’. The Tradition of Catching Finches

- Marc Argeloo – The Maleo of Sulawesi (Indonesia): The History of a Human-Animal Relationship

- Jet Bakels – BirdEyes View – A Talk with Theunis Piersma

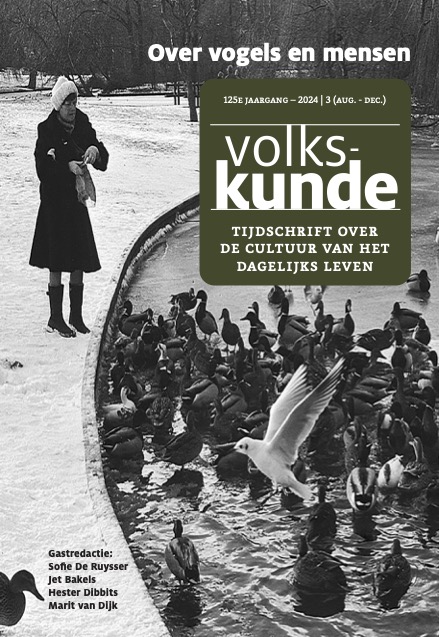

- Marit van Dijk – Feeding the Ducks – Thinking with Birds in Everyday Life

- Yulia Kisora & Clemens Driesen – Dancing with Geese

- Kester Freriks – The white stork, bringer of happiness, children and spring

Marc Vermylen – Breeding Pots: From a Local Historians’ Discovery to Bird Conservation - Riyan J.G. van den Born & Wessel Ganzevoort – How birding can strengthen environmental citizenship

- Jet Bakels – A View from the Goose’s Back. Nils Holgersson’s Wonderful Journey

- Yvette Jol & Edwin van der Veldt – The Contested Rooster of Kallemooi. A Local Tradition Under Pressure Due to Changing Views on Human-Animal Relationships

Marit van Dijk, Hester Dibbits, Jet Bakels & Sofie De Ruysser – Observations: Our every day Life with Birds

This thematic issue contributes to the ongoing discourse on changing human-animal relationships, focusing specifically on birds. Contributors explore the multifaceted ways birds are embedded in daily life, examining both traditional practices — such as egg gathering and birdwatching — and contemporary initiatives, including citizen science projects. Through a range of articles, interviews, and personal reflections, the contributions reveal the complexities of our interactions with birds and the implications for biodiversity, conservation, and cultural heritage. The discussions emphasize the necessity of interdisciplinary approaches in understanding these relationships, questioning anthropocentric viewpoints, and exploring how our engagements with birds may inform broader ecological citizenship. Ultimately, this issue invites readers to reflect on their connections with nature and to consider the role of birds in shaping cultural narratives and environmental stewardship.

Inge van der Zee-Minkes – Aaisykje: from picking to cherishing

The tradition of “Aaisykje” (searching for lapwing nests) is deeply rooted in Frisian culture. With the arrival of spring, the Frisians would head out to the meadows, searching for the first lapwing eggs – a precious delicacy – for centuries. Egg seekers, armed with a pole and a flat cap, would cross the wet fields, looking for the speckled eggs. Finding these eggs was an art, requiring knowledge of bird behaviour.

Originally, the eggs were collected for personal consumption. Later, especially during the Middle Ages, they were also used as a form of payment by tenants. In the twentieth century, a trade in these eggs developed, with the first eggs of the season fetching high prices. These first eggs were even presented to the royal family.

Shortly after World War II, the BFVW (Bond Friese Vogelwachten) was founded by nature enthusiasts to protect farmland birds. In the 1960s, the BFVW introduced the concept of “aftercare,” where nests were protected from agricultural activities after the egg-collecting season. However, the combination of harvesting and conservation efforts did not prevent criticism of the tradition. Due to increasing pressure from conservationists and subsequent legal battles, a definitive ban on egg collecting was imposed in 2015.Fortunately, this did not mark the end of Aaisykje. Thousands of volunteers continue to work each year to protect and monitor meadow birds. These volunteers, using their knowledge and passion, contribute to the preservation of nests and the broader conservation of meadow birds, giving the ancient art of “Aaisykje” a new meaning. As a result, the BFVW has evolved into a bird monitoring organization.

A final remnant of the original tradition – the honouring of the finder of the very first egg of the season – remains. For many Frisians, this ceremony continues to mark the start of spring!

Hubert Slings – ‘Die vinken en keepen wil vangen, die zinge geen psalmen of gezangen’. The Tradition of Catching Finches

As part of the bird migration, countless finches and other songbirds fly south from Russia and Scandinavia along the Dutch coast every autumn. For centuries, many of our countrymen have made it a sport to catch as many as possible. The common man does this with trap cages, glue sticks, and other small equipment. The elite had special finch tracks built for this purpose. Such a finch track can be seen in the Dutch Open Air Museum in Arnhem.

Marc Argeloo – The Maleo of Sulawesi (Indonesia): The History of a Human-Animal Relationship

The maleo is a critically endangered, chicken-sized bird species found exclusively on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. Female maleos lay their eggs on sunlit sandy beaches or in forest soils heated by volcanic activity. These birds gather in large numbers at specific nesting grounds, where each maleo egg can be almost five times the size of a chicken egg. The local population traditionally collects and consumes the eggs. Combined with the loss of their natural habitat (rainforests and quiet sandy beaches), the species is now threatened with extinction. Nesting grounds, once abundant with maleos digging holes to lay their eggs, have become increasingly rare.

The long-standing tradition of local communities collecting and consuming maleo eggs has given the species a unique status on the island. Egg collection and trading were once important sources of income for Sulawesi’s residents. These practices became ingrained in the island’s culture and traditions, with maleo eggs even being traded by local kingdoms. For instance, in 1947, during Dutch colonial rule, Uno documented the egg collection and trading customs at the Panua nesting site, where nearly 10,000 eggs were traded annually. However, in recent decades, these traditions have largely disappeared. Despite the maleo’s absence from much of Sulawesi today, it remains the island’s most well-known animal, particularly among older generations. The name “maleo” and images of the bird are still widely used for commercial purposes (such as product and store names) and can be found in public spaces (e.g., street names and statues).To protect the maleo from extinction, its cultural significance, combined with legal measures, can be harnessed for conservation efforts. Traditional egg collection and trading practices must give way to activities that ensure the species’ survival, particularly by protecting nesting grounds.

Jet Bakels – BirdEyes View – A Talk with Theunis Piersma

Adolescent house martins, spoonbills hanging out with friends, godwits as a compass for healthy farmland. Theunis Piersma achieved great fame with his meticulous analyses of the physiology of migratory birds, but he is increasingly paying attention to the characters and choices of individual animals. In addition to the age-old adage ‘measuring is knowing,’ he increasingly views birds as personalities, animals that are closer to humans than we often recognize. He advocates for a personal and emotional relationship with the nature around us—one that makes us realize we are part of a larger community. A paradigm shift? Remarkably, high tech and artistry play crucial roles in this.”

Marit van Dijk – Feeding the Ducks – Thinking with Birds in Everyday Life

This article is written midway through the research project Thinking with Birds, which explores how thinking with birds can make relationships with nature in daily urban life visible from a heritage perspective. Heritage studies have traditionally focused on (common) human values, but when other species are considered as stakeholders, this value-oriented approach becomes more complex and speculative. The case study of feeding ducks is examined. While this practice is common in Western societies, it has recently been banned in many large cities, such as Amsterdam, due to the rise in rat populations. The tradition affects various species, including plants, ducks, humans, and bacteria—each experiencing different realities yet coexisting. As the project experiments with different methodologies and concepts for a more holistic, nature-inclusive approach to heritage, this article reflects on the lessons learned and the practical applicability of these approaches.

Yulia Kisora & Clemens Driesen – Dancing with Geese

Under continuing pressures of climate change and urbanization, Barnacle geese, like many other bird species, have been changing their migration patterns and settling in new territories. These changes led the birds to enter a complicated relationship with local human residents, institutions and governments. This case study illustrates such a relationship at Korkeasaari Zoo in Helsinki, Finland, where approximately 200 pairs of wild Barnacle geese now have been nesting annually for over a decade. Inspired by the metaphor of dance, and drawing on geographical theories of encounter, we explore the embodied process of mutual adaptation, learning, and negotiation between the geese and human users of the zoo. Through a series of photos, we highlight shared affective and bodily aspects of these close and repeated encounters with nesting geese. These ‘dances’ are diverse and emotionally charged, based on power play, careful attunement and continuous mutual interpretation of the intentions of the other. We see humans and geese twisting and turning in ways involving roles such as testing, teasing, intimidating, bullying, protecting, repelling, escaping, and ignoring. We conclude with exploring the limitations of the dance metaphor, noting that in this context, dance does not require shared intentionality or close relationships. Instead, it embodies a more complex and ambivalent interaction with different goals, happening repeatedly, shaping and being shaped by the site in which it takes place. Dancing with geese produces a space where humans figure as a – however awkward and inharmonious – part of nature, rather than as distant and untouchable observers.

Kester Freriks – The white stork, bringer of happiness, children and spring

Of all the birds, the white stork (Ciconia ciconia) is one that is deeply connected to human culture and mythology. In ancient times, the Greeks depicted this large black and white bird with a red beak and red feet as the bringer of spring, happiness, and, especially, children. This enduring myth is still vivid today, both in ethnology and in everyday life. It is considered a “success story,” as it has been passed down by parents to their children for centuries. One reason the white stork is so deeply rooted in Western culture (poetry, paintings, ethnology, folklore) is its visibility. These birds live and breed close to farmers in rural areas, as well as near people in urban settings.

In the second half of the 20th century, however, the iconic white stork was nearly extinct due to the widespread use of agricultural chemicals and intense hunting. But through a dedicated reintroduction programme – carried out in the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, and Switzerland – the bird has made a comeback. There are also several pairs of White Storks now living in the United Kingdom. This resurgence can also be seen as a success story.

Marc Vermylen – Breeding Pots: From a Local Historians’ Discovery to Bird Conservation

In the 1960s, local historians rediscovered breeding pots in their collections and surrounding environments. Research revealed that these earthenware jars were once attached to building facades to provide birds with nesting spaces. Hanging breeding pots not only prevented birds from nesting inside houses but also likely contributed to controlling the populations of starlings and sparrows. The use of these pots is depicted in paintings by artists such as Hieronymus Bosch, Gerard David, and Pieter Brueghel the Elder. De Wielewaal, a civil society organization advocating for nature and biodiversity, initiated a collaboration with local potter Herman Verhoeven to design a new series of breeding pots. The sales from these pots generated additional funds for nature conservation efforts while also addressing the loss of small nesting spaces caused by increased building insulation. By providing alternative nesting spaces, the breeding pots help sustain bird populations and promote the coexistence of birds and humans.

Riyan J.G. van den Born & Wessel Ganzevoort – How birding can strengthen environmental citizenship

This article reports on findings from the European research project EnviroCitizen, which explored how citizen science activities, specifically bird counting and ringing, can enhance environmental citizenship. Environmental citizenship involves both care about and care for nature. The project consisted of three components: past, present, and future.Through historical research, we examined the characteristics of key amateur birders in the Netherlands between 1850 and 2000. We observed a shift in environmental citizenship, with a decline in hunting and collecting, and a rise in protection and monitoring over time. We also identified exclusion as a barrier to environmental citizenship in the past, particularly the exclusion of women.

To understand contemporary birding practices, our team conducted ethnographic fieldwork and in-depth interviews with birders in six European countries: Estonia, the Netherlands, Norway, Romania, Spain, and Sweden. A key finding is the self-reinforcing cycle of love, learning, and care, which explains how birders come to take action for nature. Initial sparks of interest lead to growing attentiveness to birds and nature. This attentiveness, in turn, opens up new worlds—such as an appreciation for birds’ diversity or songs—which further strengthens the motivation to learn and fosters a deeper connection with nature.

The first two parts of our project helped us understand the pathways and processes that lead people to take action for nature. However, our goal was not only to study and understand these processes but also to help strengthen them for the future. In the final section, we discuss how lessons from our research on inclusion, worlds opening up, and the emotional aspects of love and grief can be used to reinforce the connection between birding activities and care for nature. Our findings show that love, learning, and connectedness are key motivations and pathways for fostering care about and for birds and nature.

Jet Bakels – A View from the Goose’s Back. Nils Holgersson’s Wonderful Journey

In this article, we explore one of the most acclaimed children’s books of all time, The Wonderful Adventures of Nils, by Swedish author Selma Lagerlöf (1858–1940). Published in 1906, the story follows young Nils as he embarks on an extraordinary journey through (and over) Sweden on the back of a goose. Lagerlöf presents a surprisingly animal-centred perspective, partly inspired by folktales. But can children’s books also inspire Eco-Citizenship – a responsible approach to nature? It turns out that Lagerlöf was ahead of her time, depicting nature in ways that align with contemporary views, positioning humans as part of nature rather than at its centre.

Yvette Jol & Edwin van der Veldt – The Contested Rooster of Kallemooi. A Local Tradition Under Pressure Due to Changing Views on Human-Animal Relationships

The Kallemooi festival, celebrated annually on the Dutch island of Schiermonnikoog, is under increasing scrutiny for its use of a live rooster. During this traditional festival, a rooster is placed in a basket atop an 18-metre mast for three days during Pentecost. While the local community views Kallemooi as an essential part of their cultural identity, animal welfare organisations criticise the practice as inhumane. This article explores the broader context of human-animal relations and how the debate over the festival reflects shifting societal values regarding animal rights and welfare.

The article examines both the defenders and opponents of the tradition, highlighting the perspectives of local organisers, who argue that the live rooster is integral to the authenticity of the festival, and animal welfare advocates, who label the practice as animal abuse. The discussion also touches on the role of the Dutch government and heritage institutions in mediating these conflicts, as well as the impact of legal actions and public protests on the tradition.

By placing Kallemooi in the wider debate over the treatment of animals in traditional practices, the article reveals the tension between maintaining cultural heritage and adapting to modern ethical standards. It also addresses how, despite adjustments to improve the rooster’s welfare, the opposing parties remain deeply divided, leaving the future of the tradition in question.