Jeroen Reyniers

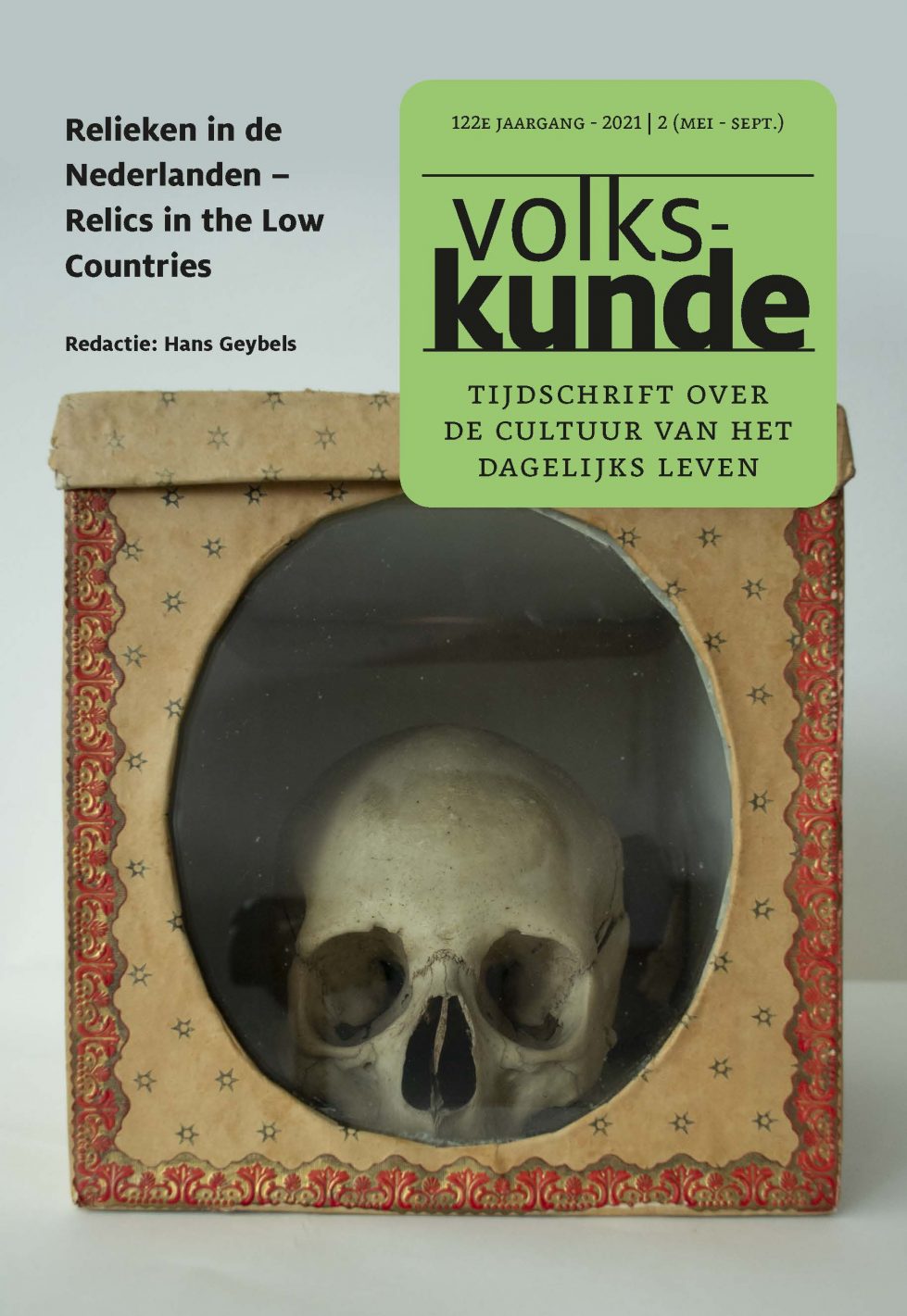

Relics and Reliquary Treasures of Saint Ursula in Belgian Limburg

Saint Ursula was a king’s daughter (4th/5th century) who was murdered together with several virgins in Cologne. Possibly due to an interpretation error of the legend the cult changed to ‘Saint Ursula and the eleven thousand virgins’ in the ninth century. This legend received renewed attention thanks to the discovery of the pseudo-relics in 1106 in Cologne. An enormous export of these bones on a large scale was a logical consequence The above article presents a status quaestionis of the relics and relic treasures of these virgins preserved in the Belgian province of Limburg. The focus lays on the bones, which have been subject to extensive material-technical studies in recent years. These relics can be found in Sint-Truiden, Tongeren, Hasselt, Kerniel, Borgloon and Maaseik. They are related to a cult that was already established in the Middle Ages and continued to be valued over the centuries. The researched cult objects can mostly be found around Sint-Truiden. Willem van Ryckel (1249-1272), abbot of the Saint Trudo Abbey, was a great promoter of the cult. Material-technical analysis proves that all relic treasures contain ancient human bones. Exceptionally, animal bone material is also found. Over the centuries, the relics were decorated with many textile fragments. Pieces of old (rich) textiles were repurposed and added to the relics. Because the textiles touched the relics, they acquired a sacred status themselves, so they could no longer be removed from the skulls or bones. The art-historical and material-technical analyses clearly indicate that they came from far and wide. This gives evidence to the then existing trade networks. The many layers of cloth added over centuries show how much the relics of Saint Ursula and the Elven Thousand Virgins were appreciated. This attests to the historical value of the relics.

Charles M.A. Caspers

The Bones of Liduina van Schiedam (1380 – 1433)

For decades before her death, Liduina of Schiedam (1380-1433) was considered a living saint. After her death she was a real city saint, but after the Alteration (1572) her veneration was forbidden. In 1615 her bones were smuggled to the Southern Netherlands, where she gained status in several places. The cult in Schiedam was revived after the return of (part of) Liduina’s relics from Brussels in 1871 and the papal confirmation of her holiness in 1890. From city saint she had become a national saint. Liduina is still a household name in her hometown, and she appeals to the imagination of many.

Evelyne Verheggen

Religious Art as Resistance and Comfort in the Eighty Years’ War. A Portrait of the Utrecht Aristocrat Family Van Haeften

From 1568, the Eighty Years’ War against the ruling Spanish Habsburgs raged in the Netherlands. After a temporary peace – ‘Het Bestand’ between 1609 to 1621 – fighting resumed in the border region of the Dutch Republic and the Southern Netherlands. The new stadholder Frederik Hendrik of Orange Nassau conquered northern parts of Brabant and some urban enclaves in Limburg. The fall of Den Bosch in 1629 was a disaster for Catholic Brabant. From the Southern Netherlands, an artists’ resistance began, led by none other than Peter Paul Rubens. Together with Catholic artists from the Northern Netherlands, he started an offensive to support and console his fellow believers. With the help of paintings, graphics (including millions of devotional prints), catholica (pious books) and relics, a moralistic, counter-reformist offensive was carried out. In 1619, the Reformed had definitively conformed to the doctrine of predestination: they resolutely rejected the Catholic ideology of virtue and good works with its heavenly reward and the Catholic spirituality and imagination. A recently discovered family portrait from 1613 of the Utrecht Catholic patrician family Van Haeften forms the starting point of this contribution. In it, Anthonius and Anna Van Haeften and their children are grouped around the crucified Christ; in the background, a procession or pilgrimage of a group of people is painted. The family must have played an important role in hiding and passing on relics of the Holy Cross, which had been venerated in Utrecht since the Middle Ages. In addition to the two parents, three nuns are depicted in the devout family portrait: Joostgen, Johanna and Elisabeth, who had entered the convent of the Victorines of Blijdenberg in Mechelen. Son Jacobus (monastic name Benedictus) became a Benedictine and later achieved fame as provost of the Affligem abbey and as author of emblematic and theological works that were translated and distributed worldwide. To embellish his abbey, he worked closely together with leading artists. Rubens painted a monumental altarpiece of the Carrying of the Cross (569 x 355 cm): it can be seen as a sign of consolation for the oppressed Catholics in the Republic, but also as a politically inspired statement against the violence of the reformed regime. The painting is now in the depot of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels. Only daughter Maria married: with the devout Catholic Pieter Schade. Through her descendants, the family portrait was passed on from generation to generation until today.

Hans Geybels

The Factory of Relics. Bulk Distribution of Relics in the 19th and 20th Century

In the historiography of relics most attention is paid to the Middle Ages and the modern era. Many pages are devoted to the Reformation because then reliquary veneration comes under great pressure and a series of critical tracts is published. Less researched, however, is the production and veneration of relics in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when relics are produced on an unprecedented scale. Just in that period, hundreds of thousands of small reliquary boxes and pictures were prepared and distributed and a democratization and domestication of reliquary took place. By democratization the author understands that relics can suddenly be acquired by a wide public, whereas in the past they were exclusively an ecclesiastical or noble prerogative. By domestication the author understands the phenomenon whereby the presence of relics is no longer limited to the sacred space of chapels or churches but is extended to the living room of ‘the ordinary believer’. The church even encourages this by multiplying them in masses and making them available via extremely cheap carriers.

Mark Van Strydonck

Dating Saints. Thirty Years of 14C Research of Relics and Related Objects: A Survey

Although relics and kindred artefacts have been studied for centuries, almost

all research studied relics from an art-historical or a religious perspective. The

material studies were mostly limited to the study of the shrine that holds the

relics. Recently however this has changed. A growing number of researchers

start to look at relics from an archaeometric point of view. Nowadays relic

shrines and their content are also regarded as objects made for a certain use,

the devotion of the saint, with a proper history. In that way the shrines and

their content can teach us a lot about the Medieval period.

At The Royal institute for Cultural Heritage the first radiocarbon dating

on relics dates to 1990. At first it was only allowed to date secondary relics,

especially textiles. But soon afterwards the first bones from shines were dated.

Very important was the dating programme on ‘Local Saints’. Relics from

saints that were only worshipped in a restricted geographical area of the Low

Countries.